The Pre-eminence of the Will in the Philosophical Anthropology of Petrus Iohannis Olivi

Projektbeschreibung:

Die Zentralstellung des Willens in der philosophischen Anthropologie des Petrus I. Olivi

Dieses Projekt bietet die erste detaillierte Darstellung der philosophischen Anthropologie des Petrus Johannis Olivi (1248-98) (Seele, Körper, Verstand, Wille, Emotionen, Sinne, Triebe und Instinkte) und ihrer Verortung im historischen und kulturellen Kontext. Das Projekt zeigte den tiefgreifenden Einfluss der universitären Umgebung auf Olivis Theoriebildung durch eine akribische Untersuchung der zahlreichen Bezüge zu Zeitgenossen und zu den Autoren, die diese beeinflussten. Dabei wurden viele Textbezüge zum ersten Mal identifiziert und detailliert nachgezeichnet. Die Untersuchung der Texte Olivis im Rahmen des Projektes hat zum Vorschein gebracht, wie sehr dieser in die akademischen Debatten seiner Zeit involviert war. Insbesondere reagierte Olivi stark auf die deterministischen Theorien, die damals an der Universität Paris kursierten. Diese sah er als Bedrohung für den Glauben, dass Menschen frei handeln können, an. Es ist diese spezifische Situation in Paris, auf deren Hintergrund Olivis persönliche Theorie der Zentralstellung des Willens gegenüber anderen seelischen Fähigkeiten des Menschen Gestalt annimmt.

Olivi bildet seine markanten Positionen mit einem Schwerpunkt auf der Hervorhebung des menschlichen Willens in der kritischen Auseinandersetzung mit denen seiner philosophischen Gegner, darunter Siger von Brabant, Thomas von Aquin, Avicenna oder Aristoteles, heraus. Das Forschungsprojekt widerlegt dabei deutlich das bisherige Urteil in der Forschung, dass Olivi nur schwache argumentiere und die Texte seiner Gegner zum Teil gar nicht sorgfältig gelesen habe. Gegen diese Wertung weisen die Publikationen des Forschungsprojekts nach, dass Olivi eine für ihn charakteristische intertextuelle Methode anwandte, um sich mit seinen Gegnern auseinanderzusetzen: Anstatt Gegenargumente aufzuzählen und der Reihe nach zu widerlegen, spiegelt Olivi einen spezifischen Text des jeweiligen Gegners in seinem eigenen Text, indem er ihn in Anlehnung an die Struktur des gegnerischen Textes komponiert und so Teile davon oder ganze Abhandlungen (Quaestiones) gestaltet.

Neben diesen methodischen Erkenntnissen ist die exaktere historische und kulturelle Verortung der Schriften Olivis und insbesondere seines Kommentars zu den Sentenzen des Petrus Lombardus ein weiteres Ergebnis dieses Forschungsprojekts. Olivis Sentenzenkommentar kann nunmehr im Paris der Jahre vor und nach den Pariser Verurteilungen vom 7. März 1277 verortet werden. In dieser Stadt war Olivi als Student zwischen 1266 und 1267 im internationalen Studienhaus der Franziskaner und möglicherweise zu einem Zeitpunkt zwischen 1271 und 1274 auch als gelegentlich Lehrender. Darüber hinaus wurde bei den Textuntersuchungen den Anspielungen auf Olivis zweite Bezugsquelle Rechnung getragen, nämlich der Kultur des Languedoc, in die Olivi hineingeboren wurde, in der er sein Studium als Franziskaner begann und die zur Radikalität, mit der Olivi die Vorrangstellung des Willens betont, wesentlich beitrug.

Project Description:

The Pre-eminence of the Will in the Philosophical Anthropology of Petrus Iohannis Olivi

This project constitutes the first body of writing to investigate closely all the different dimensions (soul, body, intellect, will, emotions, senses, drives and instincts) of Peter John Olivi’s (1248-98) philosophical anthropology, and to relate it closely to its academic and cultural context.

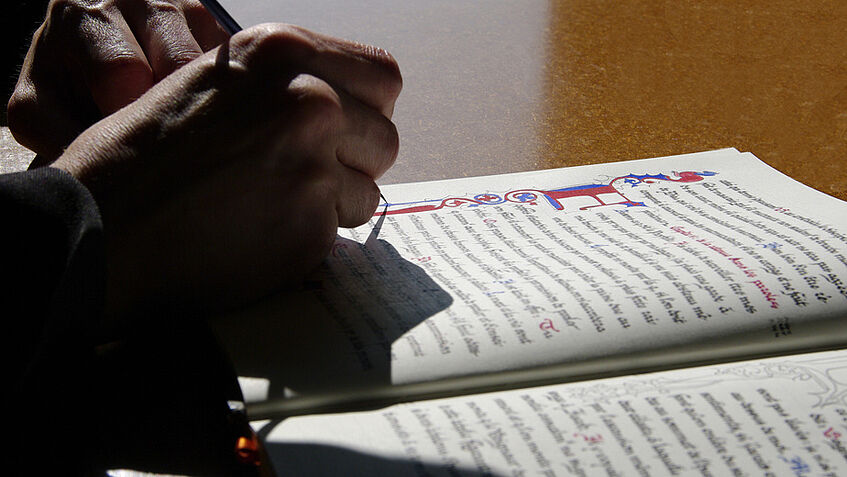

The most significant scholarly advance made in this research project has arguably been to demonstrate what was, for his age, Olivi’s remarkably original approach to criticising the positions of his philosophical adversaries in regard to the status of the will in the human subjective economy. Rather than simply summarizing the position to which he is opposed, and then presenting arguments against this position, Olivi takes a specific text of an opponent – this might be, for example, Siger of Brabant, Thomas Aquinas, Avicenna, or Aristotle – and constructs a whole question, or section of a question, as a systematic reply that mirrors the structure of the text of a chosen opponent. This text thereby becomes a form of contrapuntal ground against which Olivi frames his argument. Close analyses of how this inter-textual method actually operates have been published in peer-reviewed journals.

A second major advance made in the project has been to show that previous scholars have unjustly criticised Olivi for weak or woolly argument or, perhaps worse, for failing to read the writings of his adversaries with sufficient care. This unjust assessment has almost invariably resulted from a failure to identify the intertextual method of criticism that is peculiarly Olivi’s own.

A third advance has been to place Olivi’s writings − most particularly, the questions on human nature in his Commentary on the Second Book of Lombard’s Sentences − far more securely in their historical and cultural context. On the one hand, this is the city of Paris in the years before and after the Parisian Condemnation of 7 March, 1277. It is the city where Olivi had been a student (and perhaps also later an occasional teacher) at the Franciscan International House of Studies between 1266/1267 and sometime between 1271/1274. The close textual study of Olivi’s writings that the project has embarked upon shows just how involved he in fact was in the academic debates of the period: most particularly in terms of the project, his reaction to deterministic theories disseminated at the University of Paris that he saw as threatening the belief that human beings were able to act freely of their own accord. It is out of this very concrete Parisian environment that his own personal theory of the pre-eminence of the will in the human subjective economy took shape. The project demonstrates this profound environmental influence through both identifying and analysing, with far greater precision than has so far been done, the different voices (i.e. often concealed or implicit references to texts of his contemporaries and to those of the thinkers who most influenced his contemporaries) that inhabit Olivi’s actual texts.

The counter-balance to this Parisian environment is the culture of Languedoc, into which Olivi was born, and where he first studied as a Franciscan. Without a consideration of this environment (both as it existed within and outside the Franciscan Order), the radicality of Olivi’s emphasis on the pre-eminence of the will cannot adequately be explained. This is also shown through a close examination of the cultural implications within specific texts.